NZIBS has highlighted this story in the past. It’s worth a revisit, as many are already thinking about 2018. Are you? If so, what will you do differently next year to advance the dreams you have?

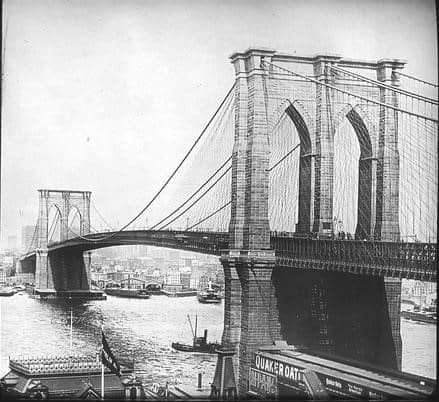

The Brooklyn Bridge in New York is one of the oldest suspension bridges in the United States. Completed in 1883, it has a main span of 486.3 m – which made it the longest suspension bridge in the world from its opening until 1903, and the first steel-wire suspension bridge. Better built than most, it survives in use today.

The Brooklyn Bridge design and construction methodology was new—in the 19th century—and the bridge was only completed due to the Roebling family’s ‘never-say-die’ attitude and total belief in their vision. In mid-century New York’s ever-increasing busyness, an enterprising engineer named John Augustus Roebling put forward a plan to build an impossibly long bridge that would connect Manhattan Island with Long Island.

Roebling, born in Prussia, moved to Pennsylvania when he was 25, to form a Utopian agrarian community and to build suspension bridges. The community failed – as most do – but his bridge designs were successful. However, when he came to New York with a bold concept to bridge New York’s East River, all other ‘expert’ bridge designers laughed. They ‘of course’ knew bridge building best and concluded that his idea was an impossible project.

“Can’t be done.”

“It’s not practical.”

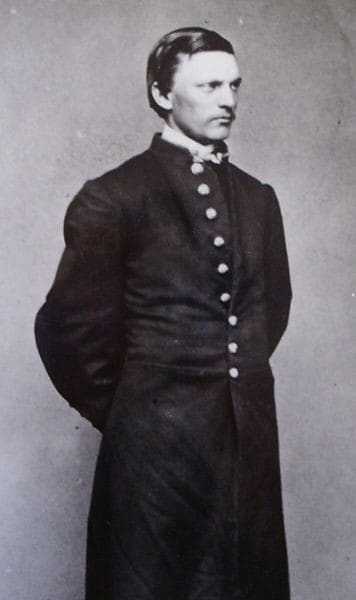

Washington Roebling

Washington Roebling

Roebling decided that no critic knew better than he did – and that this bridge could and should be built. After significant persuasion, so it was reported, his son Washington, also an engineer, agreed to help. It seemed that New Yorkers would soon be walking or riding over an engineering masterpiece. Despite many obstacles, the father-and-son duo soon completed their design for a two-tower suspension bridge. With a work crew hired, building began in 1869.

However, tragedy struck quickly. The bridge’s principal designer, John Roebling, died at only 63 after complications resulting from an injury he got while surveying the site of the Brooklyn-end tower.

His foot was crushed by a berthing ferry that pinned it against a piling. His toes were amputated. Roebling developed tetanus, but didn’t seek treatment, believing in the alternative therapies of the time. The disease incapacitated him and he died as a consequence. Washington took over the reins, although the bridge was hardly begun, and there was a long and complex road ahead. But he was young, and keen.

His first objective was to securely anchor the bridge’s two towers on the solid bedrock found under the layers of mud below the East River. To do this, builders had to work underwater.

A wooden caisson, resembling a giant box, was assembled on land, towed to the site of the Brooklyn-side tower and sunk. Compressed air was pumped into the chamber to prevent any water leaking in. The caisson’s false floor was then ripped out allowing workers to dig up the river bottom. Working conditions within the caisson were appalling. Workers could only remain on the river bottom for two hours, due to pressure from the compressed air, as well as suffocating heat, a lack of oxygen – and the general din of construction.

Then, as they ascended through the compressed air to the top of the caisson, workers suffered the crippling and painful effects of the bends – an imbalance of nitrogen in the blood which is caused by moving between environments of different pressures too quickly. At that time, little was known about the ‘bends’ or decompression sickness. It was referred to as ‘caisson disease’ by the project’s physician, Dr Andrew Smith. Many who worked within the caissons were afflicted by the bends, including the project’s engineer, Washington Roebling.

In January 1870, construction of the towers had barely begun when Washington suffered a paralyzing injury. The decompression sickness almost killed Roebling and left him unable to continue work. He was not initially able to walk or talk or even move. He was bedridden. Critics were vocal.

“We told them.”

“Stupid men and their stupid dreams.”

“It’s the height of foolishness to chase such a crazy vision.”

Everyone had an opinion. Many felt that the project should now be scrapped. Who would complete it, anyway? The Roeblings were the only ones who believed it was possible.

After Washington got the bends, he could not continue in charge of the construction. At times he could barely move.However, in spite of his handicap, he was never discouraged and still had a burning desire to complete the bridge – and his mind was still as sharp as ever. He tried to inspire and pass on his enthusiasm to some of his friends, but they were daunted by the task.

However, Washington had to relinquish responsibility for the job of overseeing construction.

Emily Roebling

Emily Roebling

It was Emily, his wife, who rescued John Roebling’s vision. For the next 11 years, while her husband Washington could do little more than watch from a window and guide her, Emily was in charge. Initially, she had no engineering or mathematical training, so up-skilled to learn the complex disciplines required. She had to learn the nature of catenary curves, and gain a good working knowledge of the strengths of materials and all the aspects of cable construction.

Emily was also a good leader, able (in the 1880s), to supervise a crew of men – and she even spoke publicly to defend her husband.

For 13 years they worked as a team. In the end, John Roebling’s vision proved more powerful than everything that needed to be overcome. The bridge was built. Emily was there at the end, to see it completed. At the opening ceremony on May 24, 1883, she was the first to walk across. Today, this spectacular bridge stands as a tribute to Roebling’s indomitable spirit and his determination not to be defeated by circumstances.

It is also a tribute to his other engineers and their team work, and to their faith in someone who was considered mad by half the world. It is also a tangible monument to Emily’s love and devotion. The Brooklyn Bridge story is one of the best examples of a never-say-die attitude. Many others, like Roebling, have managed to overcome terrible physical handicaps and achieve ‘impossible’ goals.

Often when we face obstacles in our day-to-day life, our hurdles seem very small in comparison to what many others have to face. Even a distant dream can often be realised with persistence. You can build the bridges you need in life to achieve your dreams too.

Brooklyn Bridge Trivia

The Brooklyn Bridge toll, on the day of opening, was one cent. Soon it was three cents, but not for long. Tolls were discontinued in 1911.

To ensure its survival and longevity, Roebling had over-designed his structure. His son estimated it was four times as strong as it needed to be, despite being supplied with inferior-quality steel cables during construction because a supplier wanted to make more profit.

While designing it, John Roebling claimed that the bridge wouldn’t collapse without any cables, it would merely sag. But even after seeing it finished, many New Yorkers were not convinced the bridge was safe. To prove the doubters wrong, circus showman P.T. Barnum led a line of animals – including a herd of 21 elephants – across the bridge in 1884.

– Anthony Smits Reproduced for educational purposes